originOfSoil

originOfSoilDate

Abdiel Santana

Amara Abdal Figueroa

Ana Rivera

José Almodóvar

Kidany Sellés

Lara Sánchez Morales

Rosaura Rodríguez

Steve Maldonado

originOfSoilDescription1

originOfSoilDescription2

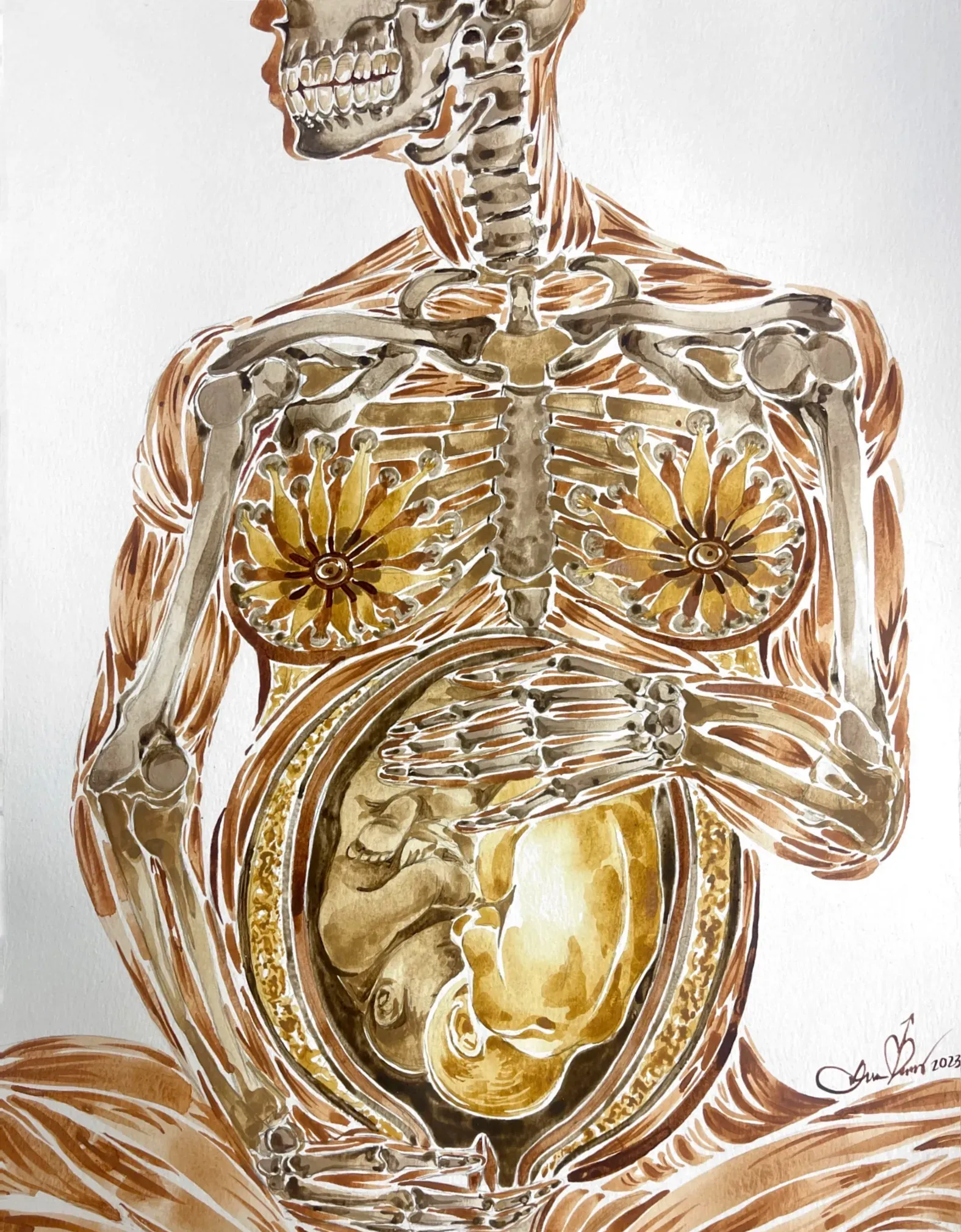

Alexandra Santos Ocasio

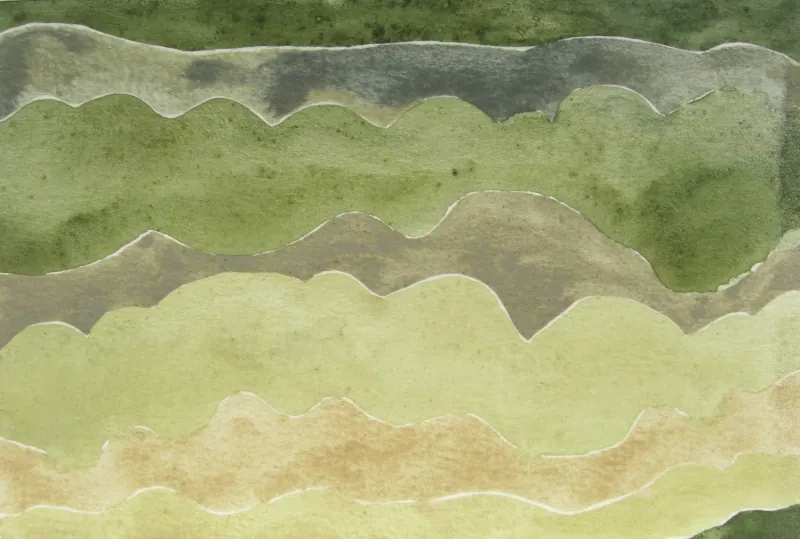

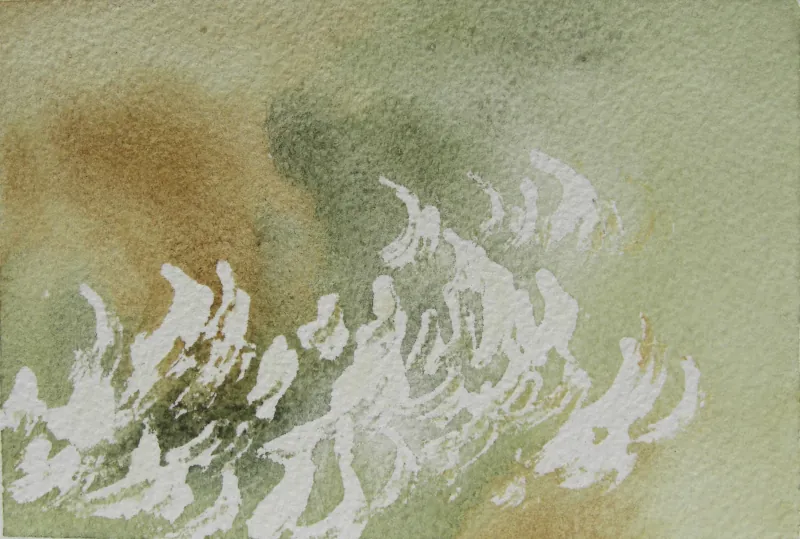

Ana C. Rivera Arroyo

Gaia, 2023

Watercolor on paper, 13" x 18"

smcCollection

Pigments:

Coto series, Oxisol order from Isabela

Rosario series, Oxisol order from Cabo Rojo

Daguey-Humatas complex, Oxisol order from Mayagüez

Cuchillas series, Inceptisol order from Yauco

Fraternidad series, vertisol order from Lajas

Coto series, Oxisol order from Isabela

Rosario series, Oxisol order from Cabo Rojo

Daguey-Humatas complex, Oxisol order from Mayagüez

Cuchillas series, Inceptisol order from Yauco

Fraternidad series, vertisol order from Lajas

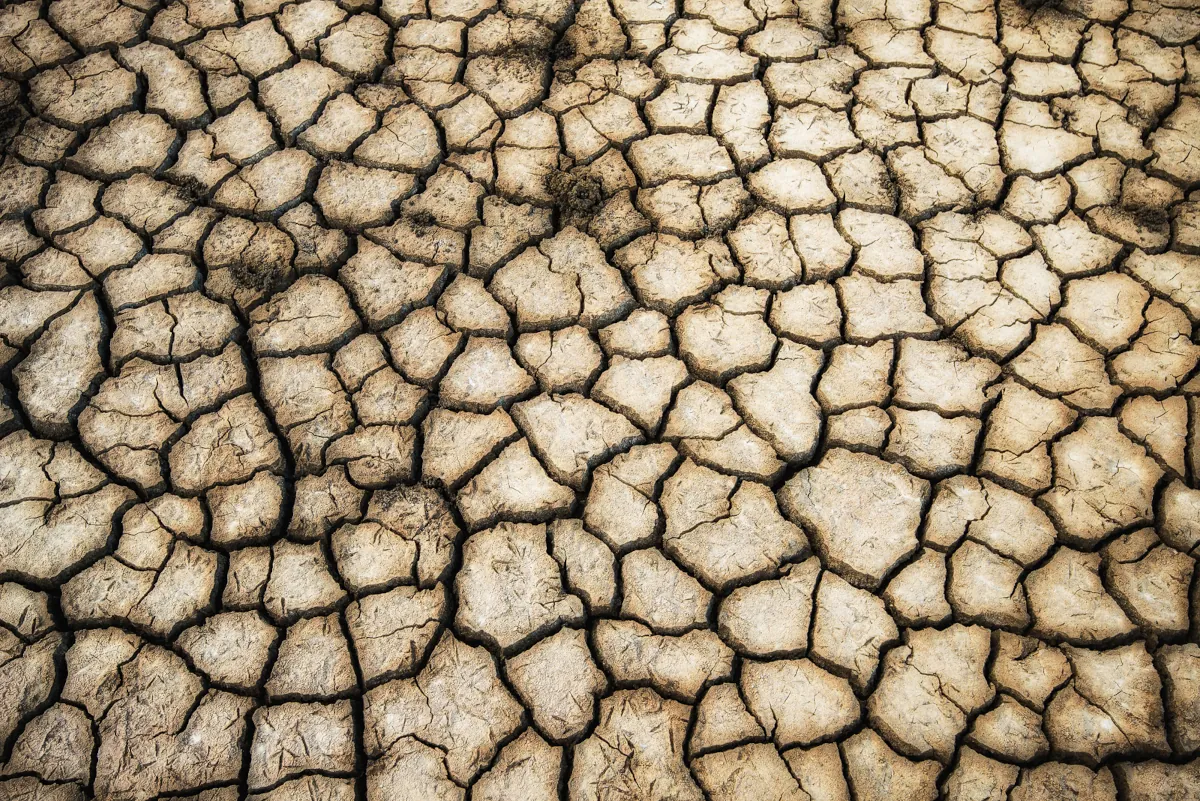

José Almodovar

- Aferrado firmemente a mi tierra ("Holding on tightly to my land")

- Añasco

- Cielo encendido ("Fiery sky")

- Desolación ("Desolation")

Digital photography

2013-2017

Courtesy of the artist

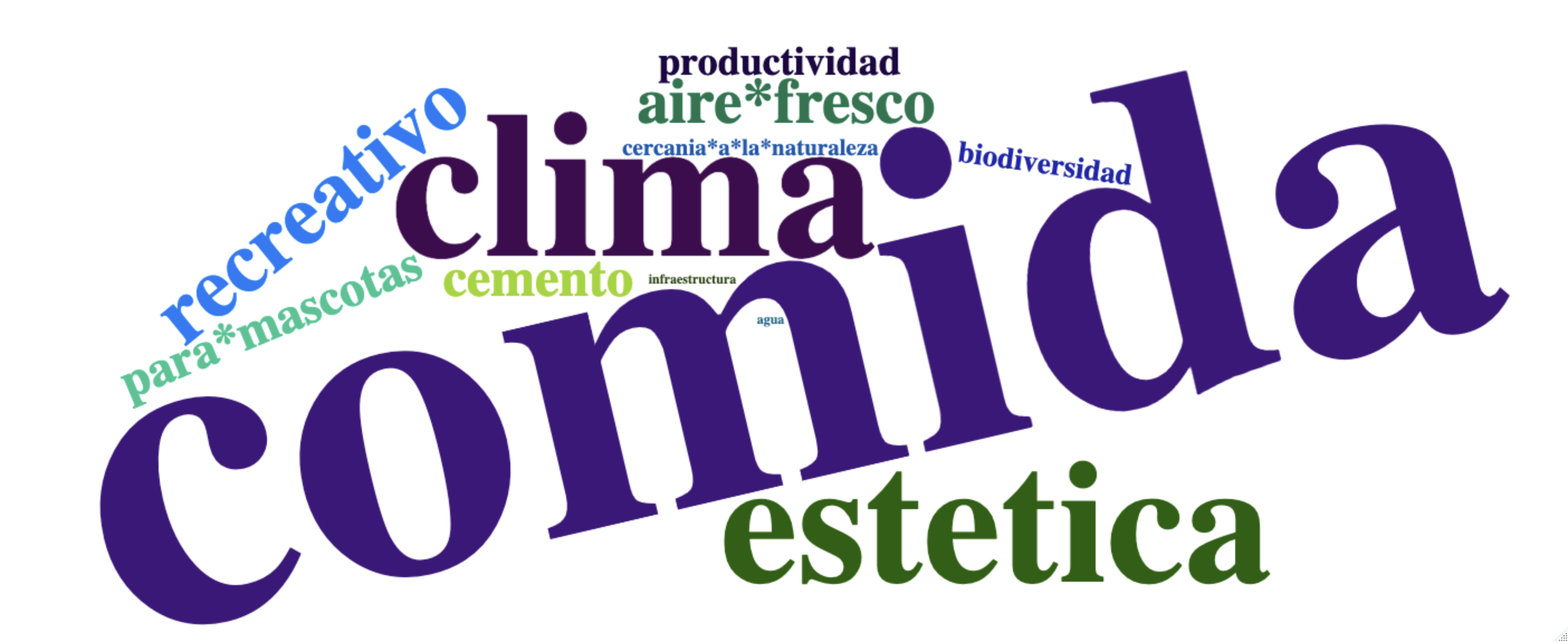

Kidany Sellés

Community response to question: Do you feel that the soil in your yard provides benefits to you and those living in the residence?, 2023

Word Cloud generated with R

Courtesy of the artist

Conducted from the perspective of environmental psychology, this study includes door-to-door surveys to collect data on how people perceive the soil of their yards in the Río Piedras Basin. The inherent properties of the soil, management decisions (i.e. chemicals that apply, and the frequency of grass cutting) and the type of ground cover (i.e. grass, shrubs, palms, and trees) were also investigated.

Some of the preliminary results suggest that people tend to value the soil in their yards less compared to other soils. This could indicate that, for the most part, soil plays a mere aesthetic role in people's backyards. On the other hand, the results suggest that the physical condition of residential soils of urban neighborhoods built 60 years ago is better than that of comparable residential soils in countries which differ in climate from Puerto Rico. This is possibly due to the fact that the development process of residential soils in the urban residential neighborhoods of San Juan is faster due to tropical conditions such as frequent rain and high temperatures. Therefore, the results suggest that the soils of these residential neighborhoods could be used for other important functions such as food production.

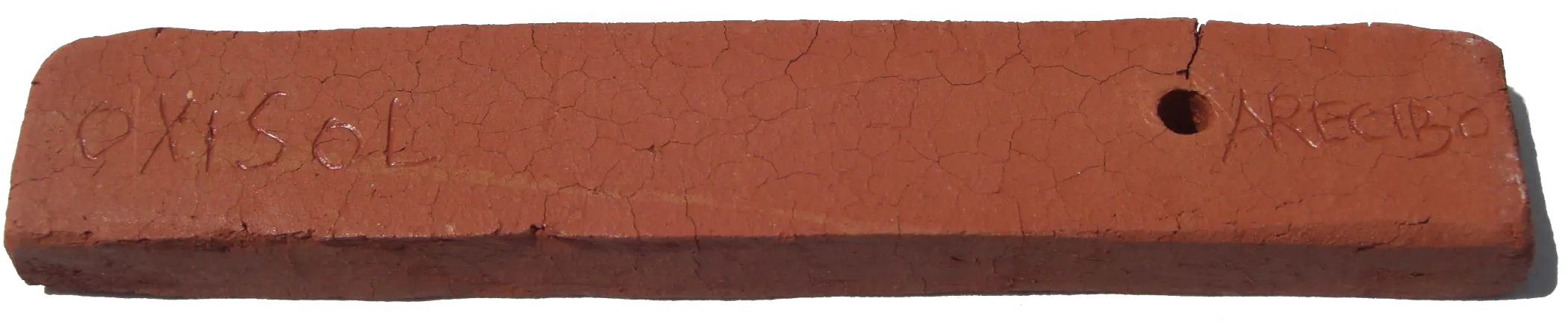

Amara Abdal Figueroa

Oxisol Arecibo, 2023

Clay burned in a wood and salt oven, 4.5" x .5" x .5"

Courtesy of the artist

Amara Abdal Figueroa

- Inclusion: Bayamón Series Thick Chamote*, 3.5" x 3" x 3.5"

- Inclusion: Bayamón Series Thin Chamote*, 2.5" x 3.5" x 2.5"

2023

Courtesy of the artist

*granular material used in pottery obtained by crushing clay calcined at high temperatures.

Nipe

Guanica

Vayas

Fraternidad

Santa Isabel

Santa Isabel

Mariana

Anones

Casabe

Cortada

Jobos

Consumo

Abdiel Santana

Geometric figures, 2015-2023

Unburned soil

Courtesy of the artist

Geometric figures act as memory vessels of the field trips carried out by the scientist-artist to describe the outstanding diversity of soils in the archipelago of Puerto Rico. Each soil with its particular name: Jobos, Santa Isabel, Mariana, Nipe, Casabe, Guánica, Cortada, Consumo, Vayas, Anones, Fraternidad. Usually named after the place they have been found: town, neighborhood or road. Intrinsically connected to our territory and communities, a soil-place or a place-soil is created.

New archaeological studies in our archipelago (and the Caribbean more broadly) have established the possibility that our ecosystems began to be altered 5,500 years ago, perhaps longer. The official history of Puerto Rico is still full of myths about precolonial societies that are reminiscent of what the American geographer William Denevan called in 1992 the myth of the “noble savage” (Denevan 1992). Both this myth and the myth of the “pristine landscapes” are based on colonial narratives that portray indigenous societies in the Americas as incapable of having had any impact on their landscapes.

Iterations of this same narrative proliferated throughout the Americas since the 16th century, and were used to make invisible the ancient presence of indigenous communities and thus justify the forced and violent displacement of their ancestral territories.

In the basins of the Río Grande de Manatí and the Río Grande de Arecibo, there are some of the oldest archaeological sites in our archipelago, from which direct evidence has been obtained of crop processing as well as soil management for different purposes associated with daily life during different times in the precolonial period.

Paleosols (soils that were formed in the past under particular climatic, biotic and social conditions) are a window to our socio-natural past that we can study to understand these ancestral processes. In the coastal alluvial plains of both rivers, a series of paleosols buried in the alluvium have been identified and these are being studied to clarify the impact of precolonial societies on them. These new perspectives serve as a people to recognize new ways of relating to the landscape, to better understand our social and natural history, as well as to propose measures for the sustainability and resilience of our soils, honoring these ancestral processes with greater knowledge.

The jars contain samples of paleosols and alluvium from the Río Grande de Manatí and the Río Grande Arecibo obtained from this study of the stratigraphy and paleosols present in these valleys. The samples were obtained from profiles exposed on the edges of each river and were then processed to date them and study their physical and chemical characteristics, including the study of the predominant ancient vegetation. Paleosols can be seen in the darker layers of the soil profile.

Lara M Sánchez Morales

Lara M Sánchez Morales

Towards an ecological history of the north-central region of Puerto Rico: 6,000 years of human occupation and landscape changes.

Documentation in digital photography and soil samples of doctoral project.

Collected between 2018 - 2019.

Processed between 2021 - 2023.

Courtesy of the artist

Rosaura Rodríguez

From the series: Native Pigments

- Rose petals, Japanese indigo, mango leaves, fresh persicaria tinctoria, indigofera suffruticosa.

- Annatto, Aibonito indigo, indigo, turmeric, kaolinite, moringa, mamey red and zinc.

- Aibonito indigo, indigo, turmeric, kaolinite and rose petals.

- Eucalyptus leaves, rose petals, indigo, turmeric, kaolinite.

Mineral and lacquer pigments on cotton paper, 5" x 7"

2021 - 2022

smcCollection

This series was created using natural pigments processed by hand by the artist in Puerto Rico. These pigments were obtained from fruits, seeds, leaves and soil samples, each collected and processed in a particular and conscious way. All botanical pigments are from the edible parts of the plants, including the binder that adheres the pigment to the surface, which also comes from a tree and is edible. Millennia of interactions resulted in the clays, rich in iron, with which paintings in this series were also created. The intention is to honor all the beings that coexist and collaborate so that life and nourishment may continue on this land.

Amara Abdal Figueroa

Component studies, 2023

Manganese and glass nodules

Clay burned in a wood and salt oven

Courtesy of the artist

Steve Maldonado

Sitio específico es tiempo específico ("Site specific is time specific"), 2017

Digital photography

Documentation of mixed media installation

smcCollection

Sitio específico es tiempo específico was an exhibition at Hidrante gallery. It consisted of a complex installation involving dead plants, live plants, and samples of each. Each plant species growing in an approximate 35m radius from the space was documented to demonstrate the diversity of this urban site. One of the interventions consisted of bringing inside an exterior garden. Another resulted from changes in the management of the gallery space. The fallen leaves of trees that were otherwise swept daily from the stairs and balcony onto the sidewalk or trash were also incorporated. The gallery windows were open for the complete duration of the exhibition, which permitted the integration of fauna into the experience. Anoles and reinitas visited the interior of the space and mingled with guests. All animals were welcome into the gallery. Several pets visited and comfortably interacted with some of the installation. Visits at different hours was also encouraged to experience 'different exhibitions'. The exhibition was an exercise and essay, affirming that site-specific artworks are also time-specific, as spaces inevitably change with time.